Farmers can trap more carbon in the ground if they protect shelterbelts and create new ones around their crops, a new University of Alberta study suggests.

Cole Gross, a postdoctoral researcher at Yale University, co-authored a study on trees, nitrous oxide, and carbon printed last week in Global Change Biology. The paper was part of multi-year agroforestry study lead by U of A soil scientist Scott Chang which involved fieldwork in Sturgeon County.

Agriculture was the fifth largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Canada in 2020, accounting for 10 per cent of the total, reports the federal government. Climate researchers say that in order to head off further floods, fires, droughts, and other extreme weather caused by global heating, these emissions must be reduced to net zero.

There is significant room for emissions reductions from agriculture, particularly from soil, Chang said. Previous research has shown how adding biochar to soil can greatly increase its ability to store carbon, and how no-till farming can reduce carbon losses from fields.

Gross said he and his team wanted to get a complete picture of how carbon cycled in and out of farm fields in Alberta.

“It’s very well established that woodlands can help mitigate climate change by storing carbon and reducing greenhouse gases in comparison to annual cropland,” Gross said, but no one knew exactly how much of a difference forests could make or what role dead trees played in the process.

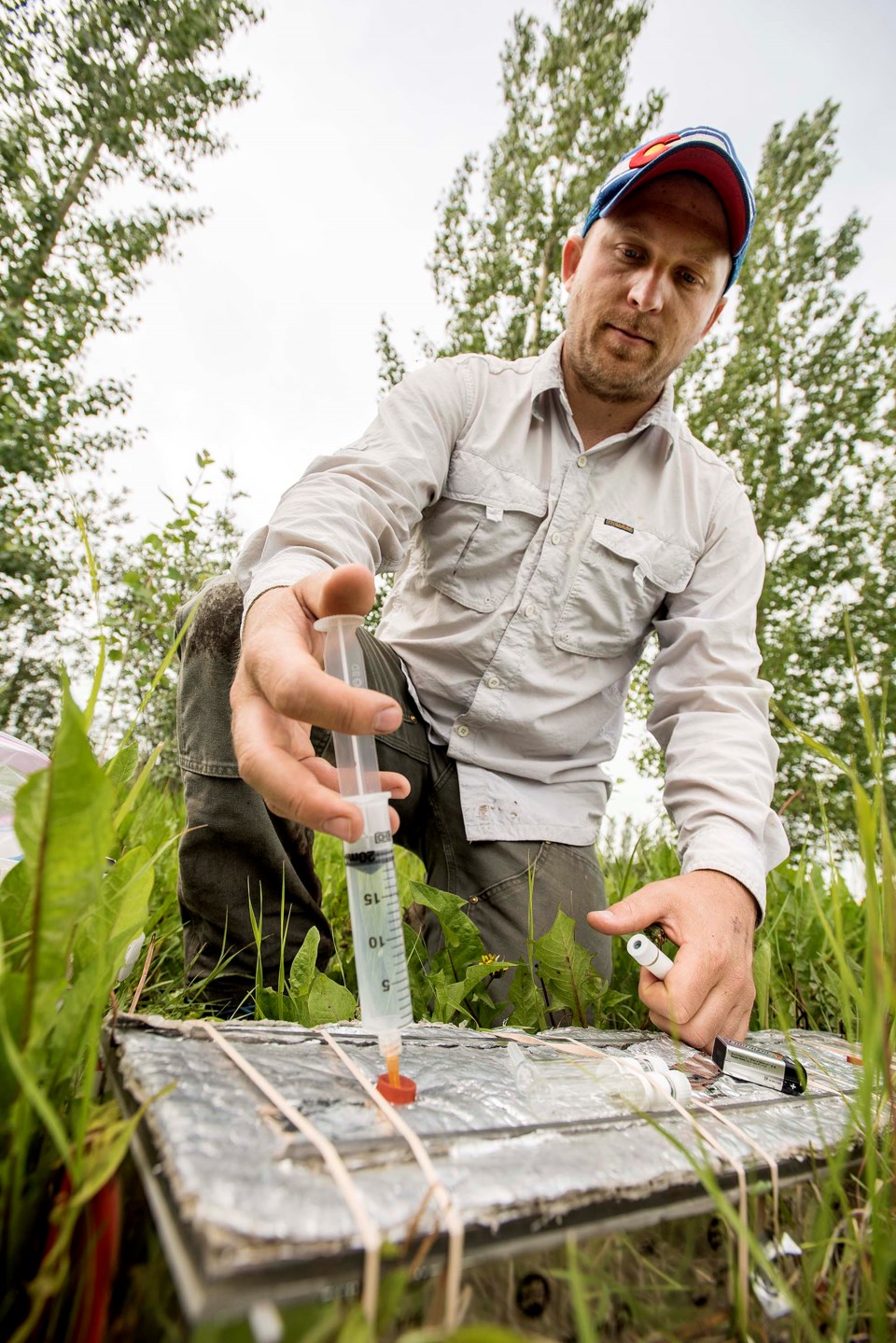

Gross and his team studied carbon stock and greenhouse-gas emissions from wheat, barley, and canola fields next to human-planted shelterbelts and natural hedgerows. This involved using an open-bottomed box to collect gas samples from the soil and analyzing the samples with a gas chromatograph.

The team found that the shelterbelts and hedgerows emitted about 89 per cent less nitrous oxide (N2O, which causes much more global warming per unit than carbon dioxide) than the adjacent fields. This wasn’t a huge surprise, said Gross — N2O comes from fertilizer, and the shelterbelts didn’t have fertilizer applied to them.

Soil samples and tree measurements showed the team how the shelterbelts and hedgerows contained two and three times more carbon, respectively, than the adjacent croplands. Gross said the hedgerows had more carbon stored than the shelterbelts because they had more deadwood in them, which appeared to be enhancing soil biodiversity.

“It’s a lot of carbon and it supports a lot of life.”

Trees add carbon to soil through their roots and the leaves and branches they drop every year, Gross said. Remove a tree and plow up the soil, and you release a huge amount of carbon all at once.

Gross said farmers should protect hedgerows on their land and plant trees in marginal areas alongside roads. Doing so would store more carbon in the ground and could create carbon credits farmers could sell.

The study is available at bit.ly/3BxEfj3.